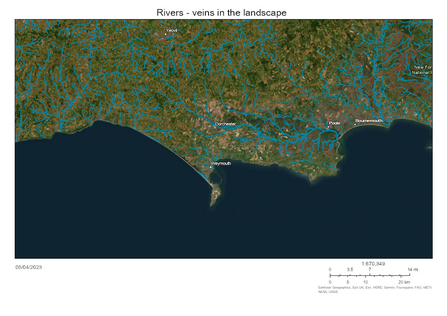

In the immortal words of Sir David Attenborough, an absolute hero of mine, “Freshwater is the lifeblood of the natural world”. Like the veins in our bodies, the network of rivers flow throughout the country bringing life-giving water. Over 200,000 km of rivers and watercourses connect our landscape, providing a lifeline for a multitude of habitats and species. However, many of the rivers in the UK are in less than prime condition, and less than half of our rivers are in a good state for nature.

Let’s take a little more of an 'in-depth dive' (excuse the pun) into the underwater lives of a few species from this week’s episode of Wild Isles and our chalk streams, the global rarity that we are lucky to have in Dorset.

Chalk streams found in Dorset are amongst the world’s rarest and most exquisite rivers. They are globally unique, representing one of the UK’s most important contributions to global biodiversity. Only around 260 of these unique rivers exist in the world, with 224 (~85%) of them found in the UK; mostly located in the south of England. They provide a rich biodiverse ecosystem, supporting important salmonid fish species including Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) and brown trout (Salmo trutta).

In Dorset the River Stour provides spawning ground for salmon and trout, and The River Tarrant, is known to be one of England’s most productive brown trout locations.